During the summer of 2019, University of Indianapolis Professor of History and Political Science A. James Fuller and UIndy Adjunct Professor of History and Political Science Krista Kinslow decided to dive deep into the crimes and history of George Mangrum.

Mangrum was an alleged rapist and murderer during the 1870s who was predominantly active in the northern Kentucky area, but committed crimes in New Richmond, Ohio that resulted in the end of his life, according to Fuller. He said Mangrum was arrested and convicted only once, in 1871, when he attacked a woman and people nearby heard her calling for help. However, he was let go early because his family was poor and in bad shape.

He was acquitted once because the victim was of “low moral and of low character,” Kinslow said. Another time was when he allegedly murdered his sister-in-law, the jury decided that there was not enough evidence to convict him and there was a hung jury, leading to no conviction, according to Fuller.

The one crime committed in New Richmond was that of Amanda Abbott, a woman who was allegedly beaten and left for dead, Fuller said. According to Fuller, this would ultimately lead to his death. He was arrested yet again, but once he was put in jail, a mob of citizens took him out and publicly hung him.

Kinslow said she first came across this case when she was researching for her dissertation back in 2018. Fuller and Kinslow said they have always wanted to co-author a book together.

“It wasn’t necessarily that we sought out to write about a serial killer. It’s more that I kind of stumbled on the story and then I realized just how much you could really spin it out in ways of understanding so many different issues [justice, gender, and sectionalism] of this time period,” Kinslow said.

Because of the age of the case, Fuller and Kinslow have faced numerous challenges while researching the crimes of Mangrum, they said. Kinslow struggled to find information on his wife, she said. She looked through census records and there was only one time Mangrum’s wife came up and that Kinslow could be sure it was his wife.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, access to records became harder because of the lockdowns and limited hours of locations, according to Fuller.

“‘The courthouse burned,’ they’ll always say, and all the records are lost, right?” Fuller said. “… But sometimes you find out that they know the records aren’t lost. They’re just stored somewhere where it’s difficult to get to them.”

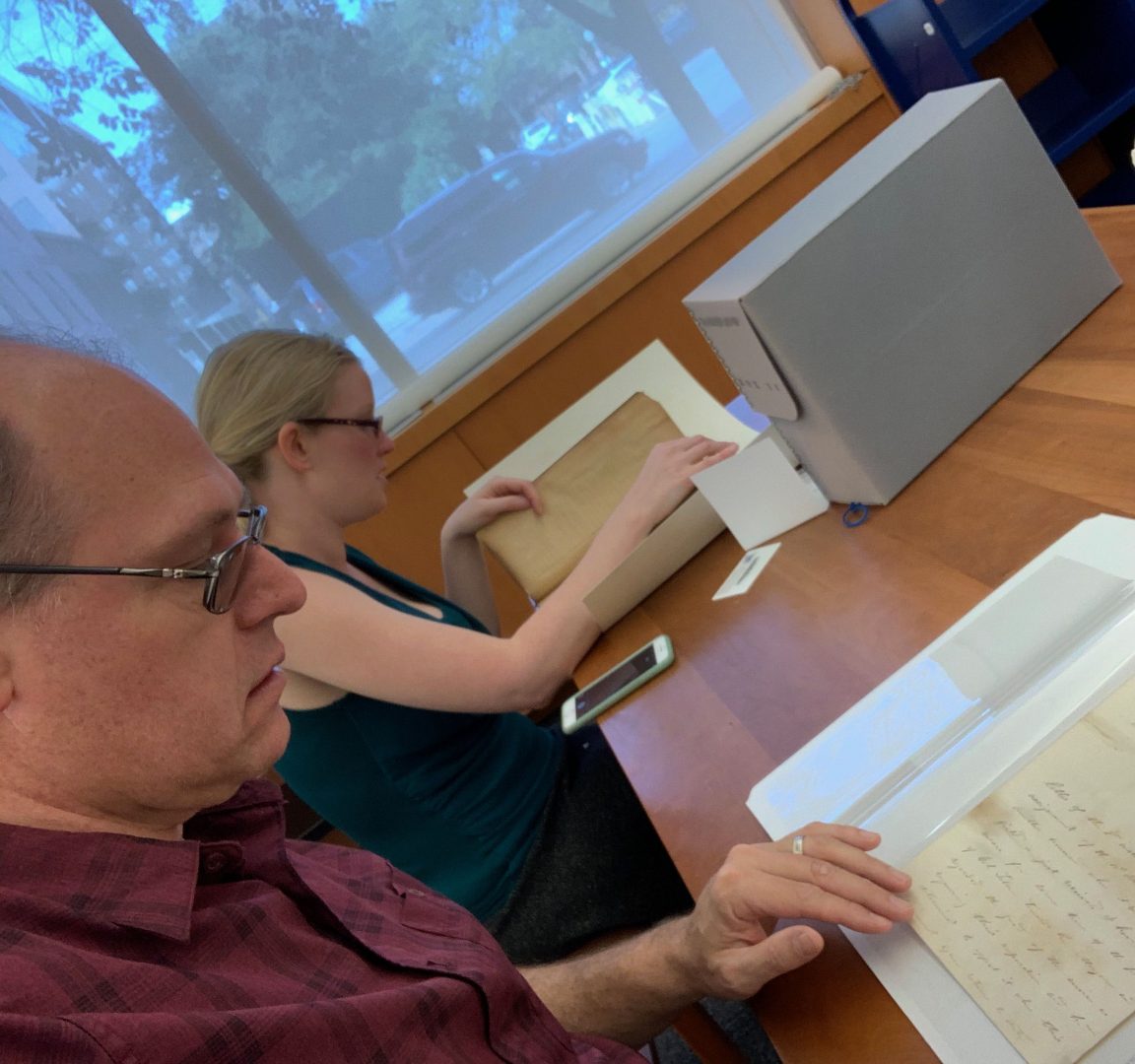

Fuller said that they are used to going into archives and looking at collections of written records. Looking at things such as letters, family items and diaries, but with Mangrum’s case it was not possible to look through these kinds of records.

“This is a different kind of enterprise, in that you don’t have those records and then [with]Mangrum … and his wife both being illiterate, we don’t have anything from them,” Fuller said. “So there’s not a letter written to him when he’s in jail, or that he wrote while he was in jail or anything like that, that you have to to account for. It’s much more of a historian as [a] detective kind of a project.”

Not only are Fuller and Kinslow relying on court records and newspaper archives but on other historians as well, they said. They are trying to learn from others about what went on this time period.

“We are in conversation with others… and I think that’s one of [the] things we want to talk about is ‘historian as detective,’” Fuller said. “But also historians relying on the work of others and reaching out to them not only to have them look at it, and say what they think is good or bad or right or wrong, but also to use what they’ve written to help interpret something that’s very difficult to interpret.”

CORRECTIONS: Oct. 27, 2020 at 8:40 p.m.

A previous version of this article did not include A. James Fuller’s full name. The article has since been updated with the correct information.