The Kellogg Writers Series, Black Student Association and University Lecture Series hosted award-winning author Randall Horton at the University of Indianapolis to read original poems and memoir excerpts to students, faculty, staff and members of the community.

D’ana Downing introduces the night’s guest speaker, Randall Horton, in UIndy Hall, Schwitzer Student Center.

Horton is the only person in the United States with both seven felony convictions and academic tenure, according to PEN America. He is also a friend of Professional Edge Assistant Director of the Arts, Non-Profit Management and Communication in the Center D’ana Downing.

“She [Downing] hit me up and asked me would I be interested in coming, then she put me in contact with Barney [Haney] and once I spoke with him we hashed it out,” Horton said.

The two met in an English classes at the University of the District of Columbia. When BSA members were pitching names of people to invite to UIndy, Downing suggested Horton.

“He [Horton] was quiet, but when he spoke, everybody listened because he had a voice that commands attention,” Downing said. “We saw him as somebody we should listen to.”

According to Horton, for about two years, he and Downing had various classes together at UDC and have remained friends since then.

During his time there, Horton was a non-traditional undergraduate student, Downing said, because he began his degree in what she believes is his 30s. He began classes at a later age due to his previous incarcerations.

While imprisoned, Horton attended a writing workshop where he read a memoir of poet E. Ethelbert Miller. This was what inspired him to pursue a new career in poetry.

Some of the pieces that Horton read at UIndy included multiple excerpts from his memoir, entitled “Hook: A Memoir.” This included a chapter that describes the character of “Hook,” an alter ego representing his past self. In its totality, the book covers the actions that he took as “Hook” and how he has changed into the person he is today.

“I wanted to read from the book and tried to select pieces that would resonate with college students,” Horton said. “That’s why it was important for me to read a section from when I was in college. The memoir spans from when I was in college to after I got out of prison.”

“I want them to understand that it doesn’t have to be the end story….”

He also read letters with an incarcerated woman identified as “Lxxx” with whom he wished to remain connected.

“I think it is very important too because women’s voices are sort of like often hidden, and we don’t necessarily get that narrative a lot, from women that are incarcerated.”

The voices of incarcerated women are a priority for Horton, which Downing said she admires him for.

“It’s one thing to have folks who have been previously incarcerated to now being published. Randall talks about how there is still room for representation,” Downing said. “He says many of the panels he is on are all men and as if women don’t exist in that space. But he is somebody who is fully promoting the opportunities and hoping to publish women who have been incarcerated and/or supporting them in their efforts to be published.”

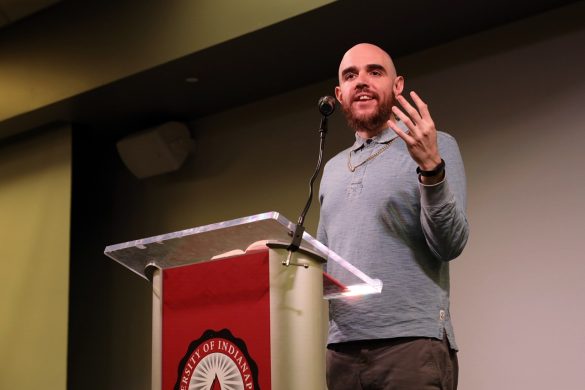

Randall Horton reads excerpts of his work from his original memoir, titled “Hook: A memoir,” on Feb. 20.

Horton said he hopes that people can learn from what he did in his life and said that “just because you took a wrong turn doesn’t mean you cannot get back on the right road.”

“I do want them [students] to understand that it doesn’t have to be the end story and there is a way out. But you have to work towards that,” Horton said. “No one is going to give it to you….You have to go create that space for yourself. But that’s what any person should do when going out into the world. Most people aren’t necessarily going to give you anything but you have to make your own way.”

Downing described Horton as a champion of the voiceless and pointed to his work with PEN America, a nonprofit organization that encourages free expression through literature, and their Prison Writing Program Committee as evidence of this.

“He talks about representation and what that looks like….” Downing said. “He is not just making space for himself but for others to come behind him.”