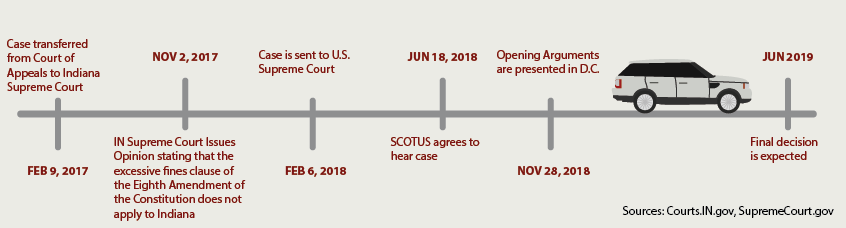

Tyson Timbs was arrested and charged by the State of Indiana with conspiracy to commit theft and drug dealing in June 2013. Timbs later pleaded guilty to one count of dealing in a controlled substance and conspiracy to commit theft, according to court documents. Timbs became involved in a related civil case, Timbs v. Indiana, which has made its way all the way to the United States Supreme Court.

The civil case started when the state seized his 2012 Land Rover LR2 after his arrest. Under Indiana law, vehicles can be seized “if they are used or are intended for use by the person or persons in possession of them to transport or in any manner to facilitate the transportation of…a controlled substance,” according to FindLaw.com.

Timbs then appealed the state’s decision to seize his car in the Indiana Court of Appeals, which found that the state’s forfeiture was excessive, according to court documents. This is because, under Indiana law, the maximum fine in this type of situation is $10,000, and Timbs’ vehicle is worth $42,000. After this, the case was sent to the Indiana Supreme Court, which reversed the Indiana Court of Appeals’ decision and said that it was not excessive because “the United States Supreme Court has not held that the Clause applies to the States.” Timbs then appealed the Indiana Supreme Court’s decision, which led to it going to the U.S. Supreme Court, according to court documents.

In the opening arguments of the case on Nov. 28 in Washington, D.C., Indiana Solicitor General Thomas Fischer said that the excessive fines clause of the Eighth Amendment did not apply to the state of Indiana because that amendment had never been applied to the states. According to University of Indianapolis Assistant Professor of Political Science and Pre-Law Advisor David Root, the main issue of the SCOTUS case, Tyson Timbs and a 2012 Land Rover LR2 v. State of Indiana, is whether or not the Eighth Amendment can be enforced against the states.

“Originally, the Bill of Rights was only applicable to the federal government, not to the state governments,” Root said. “However, through the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process clause, the Bill of Rights has been incorporated to apply to the states. It wasn’t blanket incorporation, it’s been incorporated one amendment, or one protection, at a time.”

Root said that the Indiana Supreme Court was trying to bait SCOTUS into taking the case. He said that he believes the court was doing this so that SCOTUS could confront the issues on federalism that stem from the case.

“Excessive fines, under Indiana state law, [mean that] this guy can’t be charged more than $10,000 in a fine. But when they took that truck, that truck is worth approximately $40,000,” Root said. “That’s four times the amount that they can fine him…. The issue really isn’t about whether or not taking the truck is excessive—it is. The question is ‘does the Eighth Amendment protect this defendant, and this defendant’s truck, his property, from that seizure?’ Because the excessive fine, which was originally applicable only to the federal government, is going to get incorporated to be enforceable against the states.”

If the court decides is in favor of Timbs, it could have the potential to change the laws of states across the country, according to Root. This especially would apply to those whose private property is seized as part of a crime.

“It is likely going to hamper states and protect individuals,” Root said. “Frankly, that’s what the Bill of Rights is designed to do—it’s designed to limit government and protect individuals. States are going to be against the ruling if the Eighth Amendment’s excessive fines are incorporated against the states… It takes a power play away from the state through law enforcement and the seizure of property. It would make the states less powerful vis-à-vis individual citizens.”

According to Root, the Supreme Court, under Chief Justice John Roberts, has been in favor of states rights for the last five to 10 years. Because of this, Root said, SCOTUS might decide that the protection is not enforceable against the states.

“Laws, as is, would stay,” Root said. “You may even see—the law in Indiana is that the fine can’t be more than $10,000—you could see that go up, Root said. “If they’re not going to enforce an excess fine protection against the states, state laws are either going to stay the same or they’re going to get more penalizing to someone who gets ‘guilty’ attached to them.”

The case has become a state’s rights issue, Root said, which is one of the reasons why he thinks it is important. The case has the potential to re-evaluate how constitutional amendments are applied to the states, according to Root, especially if the U.S. Supreme Court says the excessive fines clause does not apply to the states.

“…You could be looking at reinterpretation of the Constitution as applicable to the states.”

“If that snowballed to an extreme conclusion, you could be looking at reinterpretation of the Constitution as applicable to the states,” Root said. “It would be an overturning of a lot of the Warren court rulings in the 1960s. That’s where incorporation of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights to the states comes into play. If that were to happen…this case could start the process of a ‘constitutional revolution, in which an extreme amount of authority and power is shifted back to the states. Not so much away from the federal government, but away from the Constitution. That’s a big deal.”

That revolution, according to Root, would overturn cases that mostly affect law enforcement. If that were to happen, state and local police departments across the country would have broader investigative powers and abilities, Root said, especially in cases involving the Fourth Amendment, which protects against unreasonable searches and seizures and the Fifth Amendment, which protects against self-incrimination.

“One big fish in this pond would be overturning Mapp v. Ohio, which significantly hampers law enforcement’s ability to conduct searches—namely, warrantless searches—by excluding from trial any evidence secured in any search deemed ‘unreasonable,’” Root said. “Another big fish would be overturning Miranda v. Arizona, which protects arrestees from testifying against themselves both at the time of arrest and later during interrogation, provided they invoke their right to an attorney.”

Whatever the Supreme Court decides, its decision is expected to be announced by the end of the current term in June 2019.