The faculty of the University of Indianapolis is diverse in racial, ethnic and cultural backgrounds. Department Chair and Professor of English Kyoko Amano and Associate Professor of Teacher Education Terrence Harewood contribute to this diversity that can be found throughout campus.

Amano was born in Tokyo, Japan, but spent her early years growing up in Berlin and Düsseldorf, Germany. Her family later moved back to Tokyo, which is where she studied during her junior high school years.

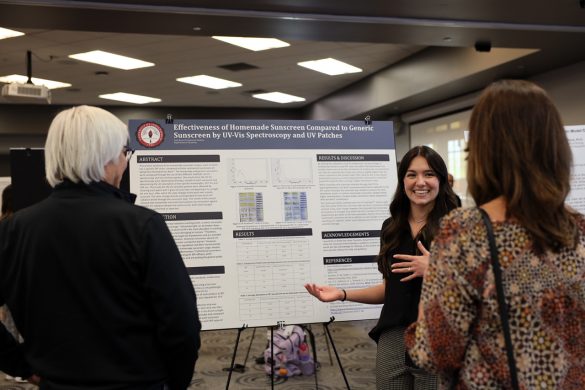

Born in Tokyo, Amano chose not to denounce her Japanese citizenship upon immigrating to the United States. Photo by Erik Cliburn

For high school, Amano decided to pursue her education in the United States, more specifically Kokomo, Ind. She later returned to Japan and earned her undergraduate degree and first master’s degree, then once again returned to the United States to study for her second master’s degree and her Ph.D.

Although many cultural differences exist between the United States and Japan, the most prevalent for Amano was the closeness of families in the United States as compared to Japanese families.

“The biggest difference … I have noticed is that in the [United] States family seems to be really close together,” Amano said. “Families in Japan tend to separate into these nuclear families more and not go back to their extended family as often. I think it’s interesting that my [high school] host family and my husband’s family stay in the same area, not going out of the state or abroad. Whereas in Japan, it is somewhat expected for children to move away to a different prefecture.”

Amano chose not to apply for U.S. citizenship. She would have to denounce her Japanese citizenship and lose the pension that she receives from the Japanese government for residing in a foreign country.

“Quite often Japanese citizens will give birth to their children in the U.S., because the U.S. says that where you are born is where you are naturalized,” Amano said. “But Japan has a different system. The family line is how they determine citizenship. So Japanese children who are born in the United States would have American citizenship. But through the family line, they have Japanese citizenship at the same time. At age 20, when they become adults, they have to decide which one they choose.”

For Amano, the hardest adjustment to living in the United States instead of Japan was adapting to the difference in language and appearance to what the “typical American” is supposed to look and sound like.

“As a professor of English, it’s particularly troublesome,” Amano said. “Because Asians in the [United] States, especially in the Midwest, are never American. You would not expect Asian people to be American. But there may be a lot of Japanese-Americans and Chinese-Americans [that] might have migrated, but aren’t accepted as citizens. The fluency in English matters so much that even though I’m really smart, my intelligence is often questioned because of the lack of fluency in English. That’s probably the most difficult part of adjusting to the U.S.”

Harewood is originally from the Caribbean island of Barbados. Because he was on the Barbados national track team, he received a track scholarship to come to the United States to study. He moved in 1990. He said that one of the most noticeable differences between the United States and Barbados is the structure of relationships in everyday life.

Harewood denounced his Barbadian citizenship to become a full United States citizen. Photo by Erik Cliburn

“Here, [the United States] people are kind of caught up in their everyday life,” Harewood said. “There are a lot of dynamics that we did at home to really preserve relationships. It’s common for people [in Barbados] to get off work or out of school and go play cricket or football [soccer] at the end of the day, or play dominoes under the street lamp until you had to go to bed. We tend to be more relationship-oriented, whereas the U.S. tends to be more task-oriented.”

According to Harewood there are only a few ways to become a full United States citizen—through refugee status, employment and through marriage. Harewood obtained his citizenship through marriage. He was given a green card and then five years later was able to apply for his citizenship in the United States. However, the choice of citizenship was not an easy one for Harewood, and it took him longer than five years to decide.

“It was a struggle for me. It took a long time to make that decision, because this is the only country in the world that actually requires you to denounce your citizenship,” Harewood said. “Most places acknowledge and accept dual citizenship, but the U.S. does not. The thought of having to denounce my country of origin and to pledge allegiance solely to the United States was problematic, because I am an ambassador for Barbados, and a lot of my foundation was there. I made the choice; I love being a U.S. citizen, but I will always put that within the context of my place of origin.”

Harewood realized one of the biggest challenges in coming to the United States was balancing conformity to the “American lifestyle” with the preservation of his own culture and background.

“The dominant pattern of dealing with immigrants here is an assimilationist kind of approach, where the expectation is that people just give up who they are and conform to the dominant values in this culture,” Harewood said. “For me that was a struggle, because I recognized that it’s important to conform in some ways, but it was it was also important for me to preserve some things that were relevant and important to my background.”

He also said another hard adjustment to the United States was dealing with the issues of racism and prejudice.

“I was encouraged to see myself as being different from people of color here [the U.S.], especially African-Americans,” Harewood said. “So I was treated differently, even in college I had professors say, ‘You guys don’t act like that…’. I never thought, about myself from a racial perspective here, because we were taught to deny it in Barbados and that was confirmed a lot when I got here. But I did have some racialized experiences and based on those, I was really able to reflect differently about my identity. It was a process and it still is a process.”

According to Harewood he visits Barbados at least once and sometimes multiple times a year, even though most of his family now lives in the United States.