The COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic’s rapid spread has led to changes to the lives of Indianapolis residents, but it’s not the first time a pandemic has affected the city.

Beginning in 1918 and continuing into 1919, one of the most severe influenza pandemics in recent history spread throughout the world, infecting 500 million people or one-third of the world’s population at that time, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The 1918 flu pandemic killed an estimated 50 million people worldwide, with about 675,000 deaths reported in the United States.

The flu, also known as the Spanish Flu or La Grippe, was caused by a variant of an H1N1 virus with genes of avian origin, according to the CDC and Human Virology at Stanford University’s website. It was first identified in the United States in March 1918 in military personnel, according to the CDC.

The flu arrived in Indiana in September 1918, according to a blog post by Jill Weiss Simins, a historian at the Indiana Historical Bureau. The Sept. 26, 1918 front page of The Indianapolis News announced that unidentified cases of illness had appeared in military training detachments stationed at the Indiana School for the Deaf, the Hotel Metropole, and Fort Benjamin Harrison in Indianapolis, according to Simins.

The army detachment at the Indiana School for the Deaf denied that the soldiers had the 1918 flu that was on the rise as more soldiers returned to the U.S. from the war front during World War I, according to Simins. 125 cases were reported in that detachment, according to the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine. In addition, 60 men were reported to have suffered from influenza in the detachment at Fort Benjamin Harrison, according to Simins. However, none of the cases had been regarded as serious.

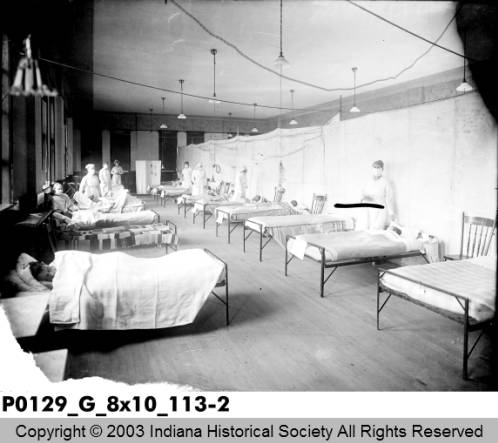

Just before the outbreak, in August 1918, the U.S. Department of War announced that the majority of Fort Benjamin Harrison would be converted into a hospital that would receive soldiers native to Indiana, Kentucky and Illinois, according to Simins. The soldiers who were stationed there waiting to receive casualties and injuries, however, ended up getting sick themselves.

On Sept. 18, 1918, U.S. Surgeon-General Rupert Blue telegraphed the head health officer of every state and asked that they immediately conduct a survey to determine how prevalent influenza is, according to Simins. In response to the request, John Hurty, Indiana’s secretary of the board of health at the time, called local health officials in each Indiana city and asked for a report.

At the time, Hurty said that the flu was contagious and that quarantine was impractical, according to Simins. Hurty also said on Sept. 26, 1918 that Indiana had not had any deaths and only had mild cases.

While Hurty was reassuring the public, both Hurty and other Indianapolis civic leaders knew they needed to do more to prepare for the 1918 influenza, according to Simins. At the time, little was known about how the flu was spread, so they tried to keep Indianapolis safe by using their intuition.

On Sept. 27, 1918, The Indianapolis News reported that prevent an epidemic in Indianapolis, then-Indianapolis Mayor Charles W. Jewett and Herman G. Morgan, then-secretary of the city board of health, to order that all public places, including hotel lobbies, theaters, railway stations and streetcars, to be cleaned, according to Simins. On Oct. 5, 1918, more cases were reported among Indianapolis residents, Morgan ordered that streetcars be operated with the windows open, along with classrooms, according to the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine.

The next day, when cases jumped by 200, Morgan prohibited all gatherings of five or more people, which effectively closed all schools, theaters, movie houses and churches within the city. Schools in Marion County, including Butler University—then known as Butler College—shut down as well, according to the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine.

In the following days, the order was expanded to include poolrooms, bowling alleys, skating rinks and “dry” beer saloons, according to the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine. Morgan also advised courts to adjourn, especially in cases that had juries. However, factories remained open and in large factories, sick employees were found quickly and sent home.

Morgan also ordered that retail stores in the center of Indianapolis have staggered hours, except for drug and grocery stores, according to the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine.

Around this time, J. K. Lilly, then-president of Eli Lilly & Company, announced he was maintaining a workforce of about 100 workers in Indianapolis and Greenfield, Indiana to work on producing large quantities of a vaccine for the flu, according to the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine.

On Oct. 30, 1918, the Board of Health in Indianapolis voted to lift the closure order and ban on public gatherings as the epidemic appeared to improve, according to the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine. On Nov. 24, 1918, The Indianapolis Star reported that 3,266 people had died in Indiana, most of whom were young men and women, and had left 3,020 children orphaned, according to Simins. The U.S. Surgeon-General Rupert Blue reported that the hospital at Fort Benjamin Harrison treated a total of 3,116 flu cases and 521 cases of related pneumonia.

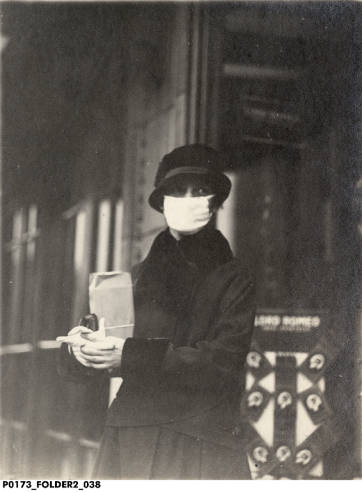

The Indianapolis epidemic had small resurgence throughout the end of 1918 and into the beginning of 1919, which led Morgan to order the wearing of gauze masks in public and to discourage public gatherings, according to Simins. At the end of the epidemic, the city had an epidemic death rate of 290 per 100,000 people, which was one of the lowest in the nation, according to the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine.

The center said that the city’s relative success was the result of how well city and state officials worked together to implement “community mitigation measures” against the flu, compared to other cities that had business interests and bickering between officials complicate their decision making, according to the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine.

The national mortality rate was higher for people younger than 5 years old, people between 20-40 years-old and 65 years and older during the 1918 pandemic, according to the CDC. The higher mortality rate for healthier people, especially those in the 20-40 age group, was a unique part of the pandemic.

At that time, there was not a vaccine or any antibiotics to protect against flu and bacterial infections, non-pharmaceutical interventions were used worldwide to control the spread of the flu, according to the CDC. Those interventions include having good personal hygiene and using disinfectants. Those interventions also included, like today, the use of isolation, quarantine and the limiting of public gatherings, according to the CDC.

For our latest coverage of the COVID-19 coronavirus’ impact on the University of Indianapolis, go to http://reflector.uindy.edu/tag/covid-19/.