Indiana’s negative public attention has subsided with the Indiana General Assembly’s fix for the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. However, the law has uncovered Indiana’s lack of civil rights protections for the LGBTQIA community and had unforeseen consequences for the state.

Leaders in Indiana academia weighed in on the issue, including University of Indianapolis President Robert Manuel. Manuel sent a campus-wide email that said he had consulted with the Board of Trustees, and they concluded that UIndy should oppose RFRA because they feared it might “impinge upon the rights of certain groups in our community.”

“Because of our mission and core values, the University of Indianapolis stands with many corporate, educational and non-profit groups in Indiana in opposition to the recently passed Religious Freedom Restoration Act,” Manuel said in the email.

Why RFRA?

The Religious Freedom Restoration Act brought Indiana notoriety with claims that the bill, now law, would allow discrimination against any person that religious individuals wished to refuse to serve. The Republican majority said that there would be no discrimination against LGBTQIA individuals or any other person based on this law.

The majority also touted a letter signed by 16 law professors who approved setting a judicial review standard, as outlined in the original bill. However, the professors made it clear in the letter that they only gave their approval for the bill’s original form. House Republican Caucus Communications Director Tory Flynn said that the professors did not give public approval for the amended bill, now law.

Democrats in the General Assembly and people across the country still believed that the bill was written vaguely enough that it could be interpreted to allow discrimination. State Rep. Justin Moed of Indianapolis joined every Democrat in both houses and four Republicans from the House in opposition to the bill.

In a statement to The Reflector, he said RFRA is a backward move for the state. Moed represents the 97th district, which includes UIndy, the Garfield Park area, Fountain Square, parts of downtown and the west side.

“The Indiana General Assembly should work to move our state forward, not backward,” Moed said. “Unfortunately, this law endorsed a kind of discrimination that many of us thought had disappeared years ago.”

The majority caucus said that a primary reason this law is necessary is because it established case law to protect from possible religious discrimination by the state. According to the RFRA fact sheet on the statehouse website, several instances exist where other state RFRA legislation has helped protect religious rights. One example described is a Jehovah’s Witness in Kansas who wanted to get out-of-state medical treatment that aligned with his religious beliefs against blood transfusions but was denied that accommodation.

Because the federal RFRA only applies to possible discrimination from the federal government, if states want to legislate how the courts should consider religious freedoms, they have to make their own laws. Assistant Professor of History and Political Science Maryam Stevenson said that establishing criteria for the courts to consider makes the outcome of religious freedom cases more predictable. She said this move in the state legislature is making public policy rather than telling the courts how to define a threshold for the compelling interest standard.

“It is still the job of the courts to decide whether the standard of compelling interest is met,” Stevenson said. “The state legislature is just setting forth a guideline.”

Future impact

The General Assembly held a conference committee to clarify that the law cannot be used by individuals to withhold services to any group, including the LGBTQIA community. This inclusion of protections against discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity is a first for Indiana in a statewide law. However, this only applies to RFRA. No other area of Indiana law provides protections based on those criteria.

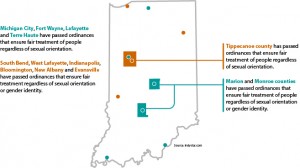

There are some local ordinances in larger cities in Indiana that offer protected status based on sexual orientation. According to the Indianapolis Star, four cities in Indiana offer protected status for sexual orientation, and six offer protected status for sexual orientation and gender identity.

Protections under these laws are limited, compared with what could be offered by a state statute. Some ordinances only offer protection in the form of a voluntary investigation, according to the Star. The Indianapolis ordinance offers an investigation, but it differs in that cooperation with the investigation can be compulsory if the city wishes to subpoena the accused discriminator, according to Indianapolis Municipal Code Section 581-421.

Neither the General Assembly nor Governor Mike Pence has expressed interest in expanding protections for the LGBTQIA community in state-level law. Stevenson said that the issue is not likely to be a priority until after 2016.

“I don’t think this is an issue the state will deal with in the near future, with the presidential election looming as a well as a governor’s race,” Stevenson said.

Although a long list of companies threatened to stop doing business with Indiana, almost all of them have withdrawn their threats following the RFRA clarification. Associate Professor of Business Law Stephen Maple does not think the RFRA controversy will have a lasting impact on Indiana business opportunities. He said companies do not settle on a location for one factor alone; they also want low taxes, a supply of skilled workers and close proximity to customers.

“Headlines evaporate really quickly,” Maple said. “I am not sure that people or companies will look at Indianapolis as tarnished. I think the so-called fix did enough to take the political sting out.”

After the Final Four, critics were back on the Hoosier hospitality bandwagon, but Moed said that Indianapolis still has some lost ground to make up in the war for public opinion.

“I am happy the governor and his supporters have seen the error in their ways, but we have a lot of work to repair the damage that has been done,” Moed said. “As a city, we must now work together to reassure the rest of the world that Indianapolis is a welcoming city that does not tolerate discrimination.”