Downtown Indianapolis was once a thriving area for Black Hoosiers, with Ransom Place as a hub for the community, according to the Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Located in a six-square block surrounded by 10th Street, St. Clair Street, Paca Street and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Street, Ransom Place is a historic neighborhood for the once-prominent African American community in Indianapolis. University of Indianapolis Assistant Director of the Office of Inclusion and Equity and Title IX Investigator CariAnn Freed described Ransom Place and Indiana Avenue as Indianapolis’ own ‘Black Wall Street.’

“In Indianapolis, it [Ransom Place] was the first community that really gathered and flourished, and it was closer to downtown right off Indiana Avenue,” Freed said. “If you drive down Indiana Avenue, you’ll actually see a placard of what’s left of Ransom Place. And it’s really just a tiny little block…. That’s where Black doctors, Black lawyers, the shops, the clubs, the restaurants, all used to live on Indy [Indiana] Avenue. You see in the progression of Indianapolis history

as you look in maps and things like that; downtown used to really be where the Black people were.”

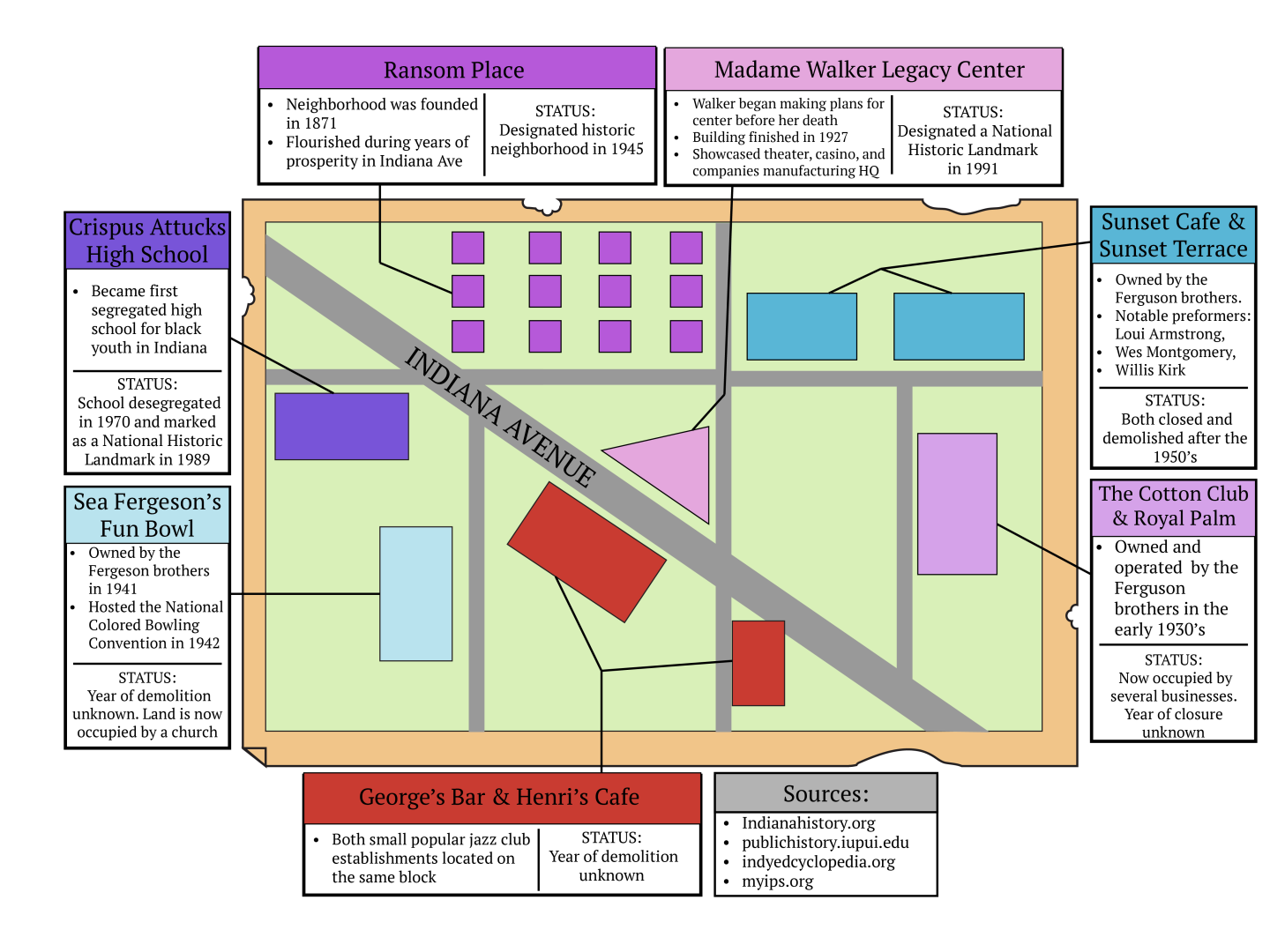

Ransom Place’s growth coincided with the establishment of Indiana Avenue, which became the central commercial and leisure district for the Black community, according to the Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. The street used to be lined by Black-owned businesses, churches, theaters and more. And while many who worked in the area worked blue-collar jobs, some residents were physicians, attorneys or even city councilmen, according to Encyclopedia of Indianapolis.

One of the most prominent residents of Indiana Avenue was Madam C.J. Walker, who relocated her business to the avenue, employing local talent and leadership to build her business empire, according to the website New America. When she died in 1919, she was considered the wealthiest self-made woman in America—regardless of race—according to New America.

However, Black residents and business owners of Ransom Place and Indiana Avenue were eventually pushed out of the area as a result of segregation, white flight, redlining and the construction of I-65 and I-70, according to New America. UIndy Assistant Professor of Sociology Colleen Wynn said redlining comes from a federal policy that influenced how home loans were insured in the past. The Federal Housing Administration and Homeowners Loan Corporation created maps based on the ethnicities, socioeconomic statuses and jobs of residents, as well as if the neighborhoods were racially integrated.

“The people here hold white-collar jobs, [and] they were, in those neighborhoods, primarily white,” Wynn said. “They were stable families, people that they [the FHA and HLC] believed would pay back loans. And so…they literally colored them [those areas] green on the map. So green was the neighborhoods where loans would be highly insured and guaranteed there…. If they felt like it wasn’t a good place to give a loan, for a variety of reasons, they literally colored them red so that when their people went to give loans, they could look at the map and say, ‘Oh, nope, we can’t guarantee a loan in that neighborhood.’”

In the 1960s, many Black residents in this area were forced from their homes when Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis systemically acquired properties to expand the university, ultimately eliminating the quality housing that was available to the Black and low-income communities, according to both Encyclopedia of Indiana and New America, respectively. Wynn said this expansion resulted in not only a loss of housing but a loss of community as well. According to Freed, who did a video project on Ransom Place, a lot of properties in the area are now IUPUI parking lots.

“That was their methodology; they would buy up these relatively cheap houses, they would demolish them all, flatten them all to the point where they were able to be a parking lot,” Freed said. “And then that would push out the next neighbor to do the same thing. At one point IUPUI was even buying moving vans to help people get out of the community faster.”

According to Wynn, these processes of redlining and the expansion of IUPUI—as well as gentrification—still greatly affect the area today, where Black and low-income residents cannot afford to live in this place that was once a home for Black excellence.

“They’re starting to be pushed out by students, or I’m sure even young professionals in some of the spaces, or perhaps faculty and staff at IUPUI maybe want to live in some of those areas,” Wynn said. “Even where there are houses and neighborhoods still, it’s not necessarily affordable for that community anymore and it’s spreading out into the other surrounding places where people were pushed to. They’re continually experiencing that, which is all tied up in some of that redlining and segregation.”

While the history of Ransom Place and Indiana Avenue is of a once bustling Black neighborhood that was uprooted by systemic racism, Wynn said it is important to acknowledge this history to prevent it from repeating.

“I think that helps us to create policies that don’t push people out and make sure that we’re recognizing how everyone has this stake in belonging there,” Wynn said. “It’s important to know about the experiences of people who aren’t necessarily like us, or who are like us who we might not know about. The history that we learn, both locally and maybe nationally in the U.S., is often told from such a white-male perspective; it’s important to make sure that we’re learning history where we can from people who aren’t just from that perspective because their experiences of an event are likely very different.”